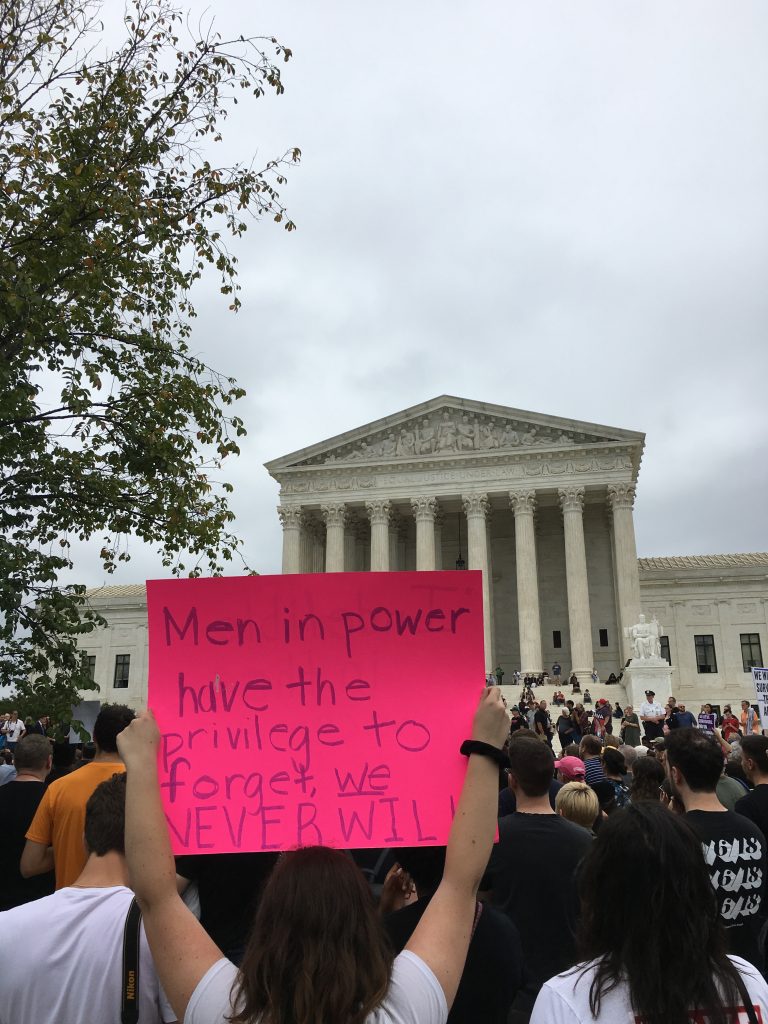

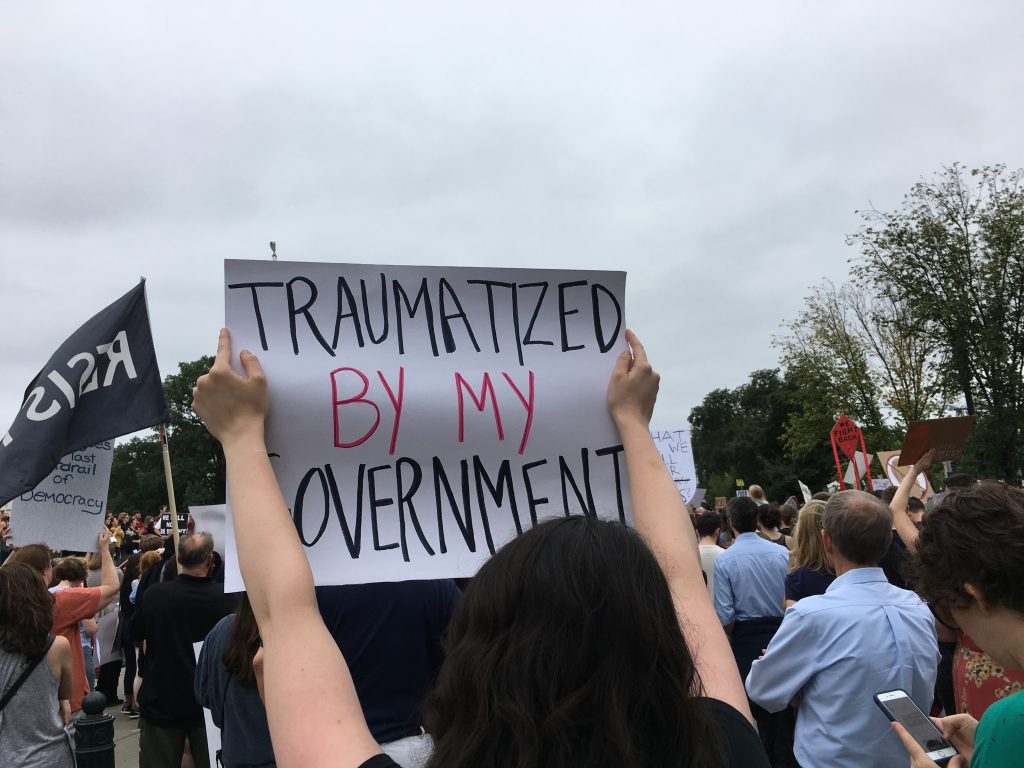

Yesterday, as an appalling process culminated with 50 Senators (who represent 44% of the population) voting to confirm the Supreme Court nominee of a president who lost the popular vote, I joined thousands of protestors outside the Supreme Court and Capitol. We heard from Senators and advocates, but most importantly, we heard from survivors of sexual assault.

By coming forward with her story of sexual assault by 17-year-old Brett Kavanaugh, Dr. Christine Blasey Ford placed her civic duty above her own wellbeing. “All sexual assault victims should be able to decide for themselves whether their private experience is made public,” she told the Senate Judiciary Committee. “Apart from the assault itself, these last couple of weeks have been the hardest of my life. I have had to relive my trauma in front of the entire world, and have seen my life picked apart by people on television, in the media, and in this body who have never met me or spoken with me.” She was not the only one to speak up about past trauma. Deborah Ramirez and Julie Swetnick shared their stories about Kavanaugh and his drunk friends, and countless other survivors — some of whom had never spoken about their assaults before — told their Senators in the hopes of averting the lifetime appointment of a credibly accused sexual assaulter to the highest court in the nation.

One survivor who spoke yesterday to the crowd in front of the Supreme Court was editor and columnist Danielle Campoamor. She conveyed the sense of betrayal many survivors feel now that the lack of justice they encountered following their own assaults has played out at the highest levels of our government. In an NBC News piece published the day before, Campoamor connected her own experience to Ford’s and that of countless others:

While testifying in front of the Senate Judiciary Committee on Sept. 27, Dr. Christine Blasey Ford said she feared her story of alleged sexual assault wouldn’t impact D.C. Circuit Court Judge Brett Kavanaugh’s ascension to the Supreme Court. “I was… wondering whether I would just be jumping in front of a train that was headed to where it was headed anyway, and that I would just be personally annihilated,” she said.

… I was 25 years old when I was sexually assaulted, and while I too feared “jumping in front of a train” that could annihilate me, I did report my assault to the local police. I gave statements, endured a rape kit, stood naked in an emergency room as a forensic photographer took pictures of my bruised body and sat through a pretext phone call in an attempt to coerce my abuser into a confession. I regurgitated the horrific details of my assault over and over again, answered questions about my drinking, my past sexual history, what I was wearing and what I said to my assailant prior to the attack.

The investigation into my sexual assault lasted over a year, and for a year my rape kit sat untouched. And at the end of the year, and once my case was finally reviewed by the local district attorney, I was told there was nothing anyone could do. It was a classic case of “he said, she said.” It was an “unwinnable case.” The train would not stop.

… Make no mistake, if I could go back I would choose not to disclose my sexual assault. Instead, and knowing what I know now, I would have swallowed my trauma and kept it buried in the pit of my stomach, if only to save myself from a pain that, in many ways, has lasted much longer than the pain of my assault.

Twenty-seven years ago, Anita Hill testified that Supreme Court nominee Clarence Thomas had sexually harassed her. The Senate Judiciary Commitee, led by Joe Biden, failed to call witnesses who could have corroborated her testimony or to guard against a smear campaign. Based on what was by all appearances a horrible experience, Hill offered concrete advice for doing a better job this time around. Her suggestions included “Do not rush these hearings” and “Select a neutral investigative body with experience in sexual misconduct cases that will investigate the incident in question and present its findings to the committee.” The committee failed to heed this advice; their only concession to investigating was a fig leaf of a reopened FBI background check, which was sharply constrained — likely by the White House — and omitted interviews with a long list of people with relevant information. Campoamor explained how such dereliction of duty affects survivors:

Every facet of our government — be it a local police department or Congress — consistently abandons the survivors that come forward; our stories are left to reverberate in our minds and replay in our dreams. Ultimately, the allegedly thorough FBI investigation into Ford’s accusations is just one more painful example of the justice system’s failures — and one more warning for those deciding whether to come forward.

The confirmation of Brett Kavanaugh to the Supreme Court imperils the Court’s legitimacy and sends a dangerous message to survivors of sexual assault. But bravery from Dr. Ford and so many others over the past several weeks, and over the past year as the #MeToo movement has captured headlines, sends a different message. Silence and complicity allow rampant sexual assault to continue, and breaking that silence forces us all to confront how our culture and institutions perpetuate it. We may have little hope of changing the composition of the Supreme Court in the near future, but we can and must change norms and policies so that the next time there’s a Supreme Court opening no one who’s been credibly accused of sexual assault will even merit consideration. We must also assure that those reporting assaults have access to justice and do not face hostility, attempted shaming, or indifference. In short, it’s time to stand with survivors.

In her speech to the crowd outside the Supreme Court yesterday, Danielle Campoamor brought up Ford’s fear that she was throwing herself in front of a train — but this time, she concluded, “We will continue to work until that train has been derailed.”

Thank you for relating your personal experience and protesting. Although many skeptics continue in their old-fashioned social rigidity, this is clearly a Public Health issue.

Bill