The death toll from Hurricane Florence has risen to 43, but life-threatening hazards stemming from the storm will persist for months. In addition to the public-health concerns that follow any major storm — lack of electricity for medical equipment and refrigeration, diseases spreading quickly in crowded quarters, mold and other hazards facing cleanup workers, etc. — North Carolina residents face health risks from coal ash and livestock waste that’s been spilling from flooded containment enclosures. North Carolina is the U.S.’s second-largest hog producer and third-largest source of poultry, with most of its livestock sector located in the flood-prone eastern part of the state.

At the many confined animal feeding operations, or CAFOs, in North Carolina, operators collect animal wastes in huge, foul-smelling pits known as “lagoons.” Even absent large storms, these lagoons subject nearby residents to horrible smells and gases that irritate eyes and respiratory systems — and, as emerging research shows, elevated health risks. A new study from Julia Kravchenko of Duke University and colleagues found “North Carolina communities located near hog CAFOs had higher all-cause and infant mortality, mortality due to anemia, kidney disease, tuberculosis, septicemia, and higher hospital admissions/ED visits of LBW infants.”

The Waterkeeper Alliance, a nonprofit that focuses on clean water, sends teams in small planes to document flood damage. Founding member Rick Dove describes some of the damage he and colleagues have been witnessing in North Carolina, and explains the problems — both after a major storm and under normal conditions:

Hogs and humans are similar enough that their waste needs to be handled with equal care. The pathogens, viruses and bacteria that swine carry can include antibiotic-resistant strains that directly affect people. Researchers have found that North Carolina industrial livestock workers carry strains of Staphylococcus aureus associated with swine, including antibiotic-resistant strains.

When waste gets into the water, it brings a deluge of nitrogen, phosphorous, copper and other nutrients that throw the river out of balance. The damage can be immediate and dramatic. In the 1990s, the pathogen Pfiesteria filled the Neuse River with millions of dead fish, bleeding from open sores, within a few days. The water turned maroon. Massive kills like that never happened before industrial agriculture came.

…Your pork, bacon, eggs and poultry aren’t as cheap as you think. Even before Florence, the neighbors of these industrial animal operations, who are disproportionately poor and people of color, suffered toxic air pollution, tainted well water, and the unbearable stench of hog manure. They’ll continue to suffer after the floodwaters recede.

WIRED’s Ellen Airhart zooms in on the issue of bacteria that’s not only disease-causing, but resistant to antibiotics:

Pig waste carries bacteria like E. coli and Salmonella, says Lance Price, George Washington University public health professor and founder of the Antibiotic Resistance Action Center. Scientists also consider North Carolina hog farms a hot zone of antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Hospitals near industrial pig farms in eastern North Carolina have found distinct strains of MRSA [Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus] among livestock farmers. “Scary bugs are going to be in the waste and in the poo,” says Price. … “We can’t afford to have a million pounds of pig shit flowing into our streams every time there’s a heavy storm.”

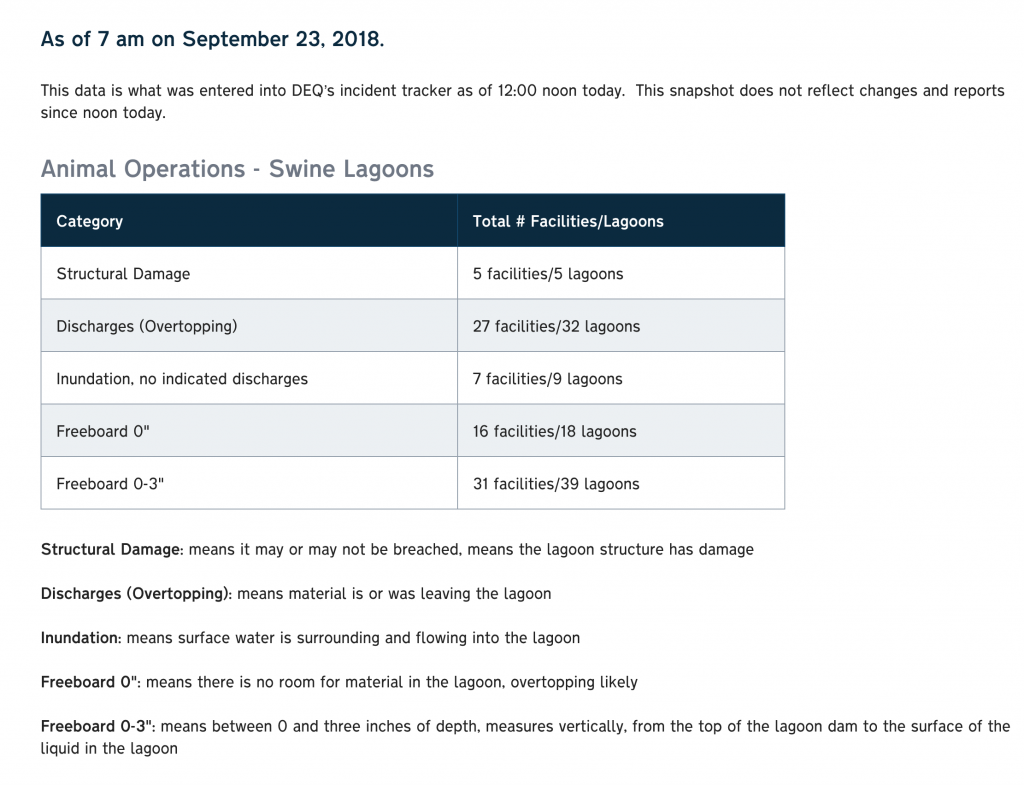

As of 7am on September 23, 2018, North Carolina’s Department of Environmental Quality reported that 32 lagoons had discharged waste; nine had surface water “surrounding and flowing into the lagoon”; and 18 had no room for material in the lagoon, meaning discharge was likely.

How can we prevent these kinds of disasters in the future, and reduce the toll on the communities that suffer from CAFOs’ impacts every day? The Union of Concerned Scientists’ Karen Perry Stillerman has some suggestions:

If Hurricane Florence teaches us anything, it’s that flood-prone coastal states like North Carolina are no place for CAFOs. At a minimum, the state must tighten regulations on these facilities to protect public health and safety. A 2016 WaterKeeper Alliance analysis found that just a dozen of North Carolina’s 2,246 hog CAFOs had been required to obtain permits under the Clean Water Act, with the rest operating under lax state regulation. The state and federal government should also more aggressively seek to close down hog lagoons and help farmers transition to more sustainable livestock practices or even switch from hogs to crops. A buyout program already exists but needs much more funding.

In the meantime, the federal farm bill now being negotiated by Congress also has a role to play. At least one farm bill program, the Environmental Quality Incentives Program, or EQIP, has been used in ways that underwrite CAFOs. In a 2017 analysis of FY16 EQIP spending, the National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition noted that 11 percent ($113 million) of EQIP funds were allocated toward CAFO operations, funding improvements to waste storage facilities and subsidizing manure transfer costs. And the House version of the 2018 farm bill could potentially increase support for CAFOs by eliminating the Conservation Stewardship Program—which incentivizes more sustainable livestock practices and offers a 4-to-1 return on taxpayer investment overall—and shifting much of its funding to EQIP.

As Emily Moon points out in Pacific Standard, past hurricanes have led to modest and ultimately inadequate changes in the state’s hog production practices: “North Carolina has had four major and deadly hurricanes since the 1990s. The floodwaters rise and recede, and public frustration over the pork industry recedes with them.” What we need now is a sustained refusal to put up with so much shit.